Caleb Woodard’s career in carving

Caleb Woodard makes his living building and carving pieces for clients around the world. He's been making special items by hand all his life, and he hasn't lost the joy of expression he has had since childhood.

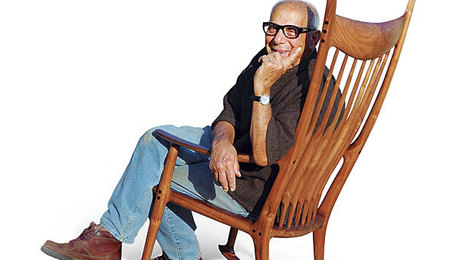

Caleb Woodard grew up in Springfield, Tenn., and after working for a spell in Washington, D.C., he went back to his home town, where he lives with his wife and their three small children and makes sculptural furniture in a small shop with a couple of assistants. His father is a woodworker, and growing up Caleb would look through his copies of Fine Woodworking, taking special note of the articles about designers and poring through the Design Books. “That’s what really drew me,” he says, “articles about Esherick and Maloof and Castle and Nakashima. Judy McKie. People making big ripples. Looking at those was a really formative thing for me.”

The following comments are excerpts from an interview with Caleb in August, 2020.

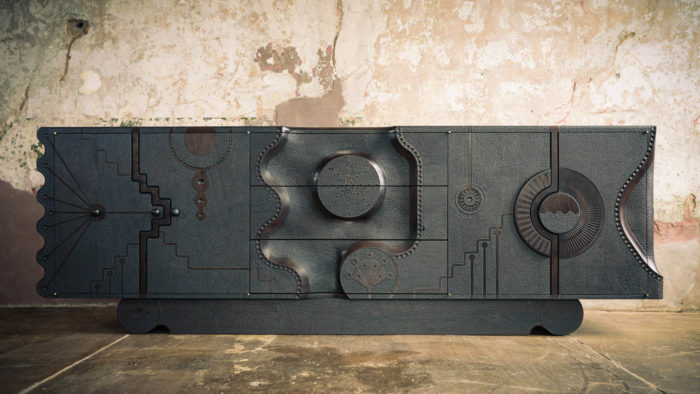

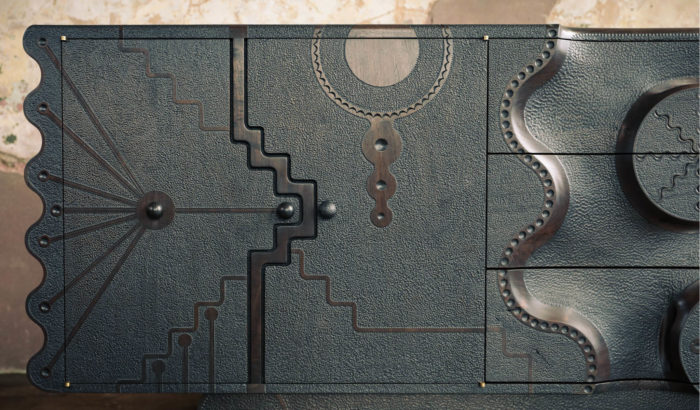

Maybe half of the carving I do is drawn out beforehand, often full scale. I lay out the majority of elements. Once I have it on paper, I transfer the layout to the material. Sometimes it feels like I spend as much time laying everything out as carving it. My work is not spontaneous, it is very measured.

With case pieces especially I have a fair amount worked out in advance in terms of construction and joinery. Although I have a lot figured out, I do leave other things to be resolved as I go. I try to leave some possibility for editing as I build—that’s where a lot of exciting stuff happens.

My father stopped doing woodworking full time when I was young, but he kept his shop and kept making things—he was always making things. Everything in our house was handmade. Spoons, toys, Christmas ornaments. As a kid I drew, painted, made things. We were only allowed to watch one hour of TV a day. So you could read or draw or make something or go outside. I used to love to make spoons and give them as gifts.

I got a degree in business. I never thought you could make a living making furniture. After college I moved to DC and worked for a trade association that promoted patio furniture and barbecue equipment. I was there seven years. But I kept making things; I made all my own furniture. I took some sculpture classes and then worked part time in a shop. I would take off my coat and tie at the end of the day and work in the shop in the evenings.

Soon I started getting clients of my own. And one year I was asked to enter a juried craft show in McLean, Virginia. I made 10 or 12 pieces of furniture for the show, and almost all of it sold. From that one show I got a steady stream of word-of-mouth referrals. I went part time at the trade association. And then 15 years ago I went full-time making furniture. I didn’t want to work in an office anymore. And then seven years ago, after our first child was born, we moved back to Tennessee and I set up shop here.

For someone starting their own business, having worked in a service industry is a big advantage. I worked my way through college waiting tables and doing woodwork and carpentry. I’ve roofed, framed, done trim carpentry, built decks, done concrete work. If I were running a design school, I would require every student to work in a service industry for a year. There’s no reason a person can’t be incredibly creative and still answer the phone politely. I set three reminders for each call and meeting on my schedule.

Carving and shaping have always been there in my work, but not fleshed out all the way. In the early years I was trying to understand what had been done by others; but most importantly trying to understand what my thing was. You need to figure that out and build on it. But how do you separate out all the noise? The trick is to tap into what’s deep inside and develop it. Don’t try to be original. Be good technically and let the originality come. If there’s something inside you it will come out.

A lot of the stuff I do is a return to childhood, in a way. Mostly in just not being afraid. Being joyfully expressive without worrying about how commercial something is. Picasso has a quote about how an artist has to return to childhood.

They say that experiencing art is the process of taking someone else’s perspective and trying it on for size. Whether it’s a Pollack or a sideboard, that’s what people are doing. So if I want people to see from my perspective, I need to make my own perspective clear. It’s the only way to stand out and to do something significant.

It’s kind of a different mindset from doing woodworking for the love of the process the way most woodworkers do. This is a different animal. But I definitely enjoy the process. And wood is the medium that I know. Some of my work celebrates and recognizes the material, but in other pieces it’s just a means to an end. Sometimes you’re trying to overcome the material, other times you’re working hand-in-hand with it. Nakashima celebrated the wood. For Wendell Castle, the material just happened to be wood. I like going back and forth between those two types of work.

A lot of my low-relief pieces have to some extent an allegorical meaning. I call this one Nocturne. It’s an idea of dreaming. I work through the meaning as I draw. I try to work out the things I’m wrestling with. Everyone is always wrestling with something.

I’ve discovered that if you really have something to say in your work it doesn’t matter what it is. People know you’re saying something. I attribute the success I’ve had to the fact that I really try to say something. When you’ve made something very intentional a person will look at it and understand it through the lens of their life. In a way, it doesn’t matter what I have to say; they give it a meaning, and it’s theirs. That’s such a neat element of making an interactive thing. Once when I delivered a cabinet, the client asked me to explain the meaning of it, and I said, “I would rather you look into that yourself.”

|

|

|

|

|

The NakashimasFEBRUARY 1, 1996 |

Comments

wow, incredible work. How you do that?

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in