Cooper’s planes

Making a barrel takes a number of planes, each perfectly adapted to a cooper’s work shaping curved surfaces.

Coopering is an ancient trade, well known to the Romans and mentioned in the Bible. Before cardboard and plastic, barrels, firkins, and hogsheads were the universal containers. Beer, whale oil, dry goods, fruits or nails, they were all shipped in barrels easily rolled along wharves or into wagons. The village cooper used the same methods and tools to make sap buckets, milk pails, churns, water tubs, and more. Every village needed a cooper. Although the trade is much diminished today, coopers are still at work fashioning tubs and barrels for aging wine, whiskey, vinegar, and hot tubbers.

To make a barrel takes a keen sense of measuring by eye and knowing your materials—how they will respond to the shaping and steaming needed to bend them into the characteristic bulging shape. Each barrel is made to hold a specific measure, liquid or dry, which requires a certain number of staves of a length, taper, and bevel to fit together tightly. Making and fitting the hoops is a challenge, too. Hardest to make are watertight barrels, strongly bulging and made of stout staves to withstand the pressure of fermenting liquids and the rigors of shipping. Less demanding are coopered barrels for dry goods, or the so-called “white coopering” of pails and churns. While some of the necessary tools are familiar to the carpenter or furniture maker—a jointer plane or drawknife, for example—most fit the needs of no other trade.

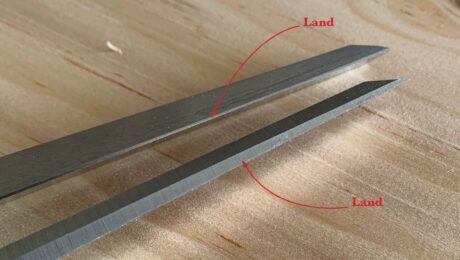

“Wet” coopers usually work with green wood, preferably straight-grained and split-out white oak. It bends well, is tough, and resists rot. The cooper shapes the staves with a drawknife and ax and puts them aside to dry to reduce any shrinkage that could open up the joints later. By eye, he cuts the tapers and bevels on each stave, pushing them over a long jointer plane used upside down and with the toe end raised on a small stand (see the photo above). Although the plane looks and works like a carpenter’s jointer, its great length (up to 6 ft. and more) and heft make it easier to bring the work to the tool. The taper of each stave defines the eventual shape of the barrel; the greater the taper toward the center, the more pronounced the bulge and the stronger the finished barrel.

The next step is to draw the staves together at one end with temporary hoops and place the barrel atop a blazing kindling fire built in a metal basket called a cresset. The heat and moisture in the wood (plus an extra swabbing of the inside of the barrel) soften and steam the staves. The cooper drives on more temporary wooden hoops to bring the staves together in the shape of the completed barrel. With a drawknife or adz he then bevels a “chime” or chamfer around the inside edges at both ends. The chime helps the barrel take the abuse of shipping without worry of breaking away the short grain where the head joins into a groove cut just below the chime. The cooper then levels the top and bottom of the barrel with a plane resembling a curved jack called a topping plane.

Next follow two tools that are unique to coopers, a howel and a croze. The howel is really no different from a compass-soled plane attached to a large curved fence that rides along the top of the staves (see the photo above). The howel cuts a smooth shallow hollow, to give a level place to cut into with the next tool—the croze that cuts a narrow groove for the barrel head. The croze has a similar wide fence that rides on the ends of the staves, but with either a saw-tooth type cutter or two nickers and a single tooth like a router plane. The head that fits into this groove is made up of two or three boards doweled together and smoothed with a large shave called a swift. The cooper cuts the edges to a fine bevel to fit snugly into the groove cut by the croze.

Before setting the barrel head, the cooper smooths the inside surface of some barrels with a stoup plane and an inside shave (or inshave). A stoup plane has a convex sole in both directions to work within the doubly curved staves. The cooper smooths the outside with a downright, another large-handled shave, and a similar scraping tool called a buzz. The final step is to fit the head and drive on wooden or steel hoops.

Making the barrel has taken a number of planes similar but different from those of other trades, each perfectly adapted to a cooper’s work shaping curved surfaces. And if he has done his work well, the barrel will hold the exact amount of liquid and not leak.

Excerpted from The Handplane Book (The Taunton Press, 1999) by Garrett Hack.

Excerpted from The Handplane Book (The Taunton Press, 1999) by Garrett Hack.

Available at Amazon.com.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in