Designer’s Notebook: Greenwood utensil design

A well-designed, well-made spoon is a joy to use, and that's one reason why Emmet Van Driesche thinks the craft of spoon carving has had such a resurgence of late.

Synopsis: A well-designed, well-made spoon is a joy to use, and that’s one reason why Emmet Van Driesche thinks the craft of spoon carving has had such a resurgence of late. Each year he includes about 30 different spoon designs in his repertoire. Here, he explains some of the challenges and joys of coming up with the perfect utensil.

Sooner or later in everyone’s woodworking journey, they feel drawn to try carving a utensil of some sort. The initial focus is on tools and technique. As you begin to have some control over the process, your mind naturally turns to design.

Form, function, and feasibility

Spoon design is likely a big part of why the craft has experienced such a surge of interest recently. Spoons are intimate objects, interacting with our hands and mouths, with dishes and pots and pans, and with food. Even a poorly executed spoon can be used. A well-designed, well-made spoon is a joy to use.

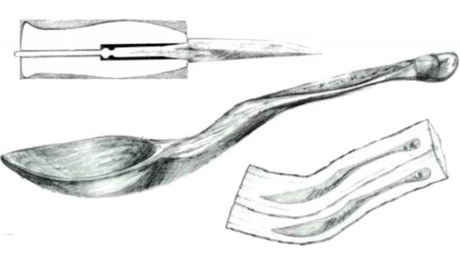

I break the design of my utensils into three categories: form, function, and feasibility. I want the shape to excite me aesthetically, I want the item to work well, and I want to be able to carve it relatively easily. The best designs come when all three aspects are intertwined, where the detail that makes a piece interesting is the same one that makes it work well and is also created by an organic part of the carving process.

Fine-tuning the design

I started out carving one-off spoons. Each was different from the previous one, and I would rack my brain each time to come up with something new. Eventually I settled on designs I felt good about for different types of spoons, and my work started to diversify, with established designs slowly evolving and new ones springing up as people asked for them. Now I carve more than 30 spoon designs, and each year I explore a dozen more. The same sequence has held true for all the different utensils I carve.

Finish Greenwood Spoons Like a Pro

In this video, Emmet demonstrates how he finishes

his greenwood utensils by burnishing them.

As this process has matured, I’ve come to some understandings about utensil design. For one thing, most eating and cooking spoons exist in the middle zone of size, and designs for especially large or small spoons come with specific challenges. With small work, there is less room for adjustment, making it more difficult to get exactly the shape you want before you run out of wood to remove. A teaspoon or baby spoon has very little wiggle room. With big designs, the challenge is to get a clean line on a bigger circumference where there are more opportunities for the knife to wobble. With wide spoons, it’s especially difficult to line up the handle symmetrically in the middle. With narrow designs, it’s harder to get the bowl and the handle lined up with each other.

The more geometric the shape (like a round bowl), the harder it is to achieve, because your eye will pick out the irregularities. On the other hand, irregular shapes and curves live and die based on extremely subtle differences that you must train your eye to recognize. A slightly squashed round bowl shape, for instance, is more forgiving to carve than a true circle, but it’s also more difficult to find the sweet spot where all the elements come together. This chase—whether you’re working on a spoon, spatula, ladle, knife, or other piece—is a big part of what makes utensil carving addictive.

Finally, you need to take into consideration how you’ll actually carve the design. Sometimes certain design choices make sense because they are very forgiving to carve, allowing you to adjust all of the other details as needed. Other times, you choose to pursue a certain form despite the fact that it is harder to pull off. This part of the

process relies on a wealth of experience: knowing exactly what you can get your tools to do, and also what you can expect the wood to do. Particularly large and small designs often push the tools right to their limits, so you need to know where those limits are and how to approach them without going too far.

Beyond the spoon

A number of the forms I carve push all three of these elements to the limits of my ability. Take my ladle design, for instance. It is a huge piece, so I need a great deal of power and stamina to pull off some of the cuts, and I need to know in what order to remove the wood so that the whole thing resolves into delicacy at the same time. Getting the form symmetrical and clean is made difficult by both its size and its width. Achieving the right geometry is a dance balancing what my tools can handle, what physically works for a ladle, and what the wood is willing to do. Finally, making the bowl thin enough is a target that moves as I carve more of this form and I become more familiar with how far I can push it.

Carving something as small as my bubble scoop presents different challenges. Visualizing two overlapping circles, one perfectly round and one slightly squished, is tricky. Trying to hold something that small is tricky too, and the size means that I have fewer opportunities to tune up the shape.

What I hope this all conveys is that utensil design isn’t just the part at the beginning where you doodle ideas on paper. Design choices are made throughout the carving process. Quite often I will adjust my plan to the reality of the particular piece of wood I’m carving, adapting my vision to what is actually possible. Rarely do things go completely as planned.

A great utensil design is electric, playful, yet seems somehow inevitable. The balance of weight is spot on, in all three dimensions. The proportions and curves are just right, and the tool finish is confident and fluid. Achieving this in a number of different forms takes experience and practice, absolute control of your tools, and a knowledge of how far you can push both tool and material. The good news is that the pursuit of this never ends, and is just as fun for spoon No. 2 as it is for spoon No. 2,000. No matter where we are in this journey, we are all chasing the same feelings. We will never quite get there, but then again, that is rather the point.

Emmet Van Driesche is a professional spoon carver, publisher of Spoonesaurus Magazine, and the author of Carving Out a Living on the Land (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2019).

Photo: Michael Pekovich

From Fine Woodworking #291

|

Finish Greenwood Spoons Like a Pro |

|

Making Wooden Spoons |

|

Knife Work |

Comments

In the photo, what are the two utensils 2nd and 3rd from the left? The ones with the slot ion them.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in