Making Sense of Handplane Numbers

Handplane aficionado Garrett Hack unlocks the mystery of the Stanley plane-numbering system.

Stanley’s plane-numbering system has had collectors confused for decades. While it might appear orderly, some numbers seem to have been assigned as much by whim as by logic. How do you explain why a #5-1/2 is larger than a #5, but a #5-1/4 is considerably smaller than both?

It all began with the first catalog of January 1870, which offered a line of cast-iron bench planes numbered 1 through 12 and wood-bottomed planes numbered 21 through 37. As new planes were developed they were generally given new whole numbers, unless they were intermediate sizes of existing planes, or nearly identical with only slightly different features (such as tilting handles). That’s why we have a #4-1/2, #9-3/4, and #10-1/4, to name just a few.

At least twice Stanley gave different planes the same number (#80 and #90), while for some reason #14 and #38 were never used. As the first hundred slots filled, Stanley used a new numbering logic: Similar tools jumped by 100, such as routers #71, #171, and #271 (and we have a #71-1/2, too). The Bedrock line jumped to #602, #603, #604, etc., the Stanley Victor was banished to the 1100s, and the Handyman to the 1200s. This left plenty of classy numbers such as #444 to assign to the only dovetail plane on the market.

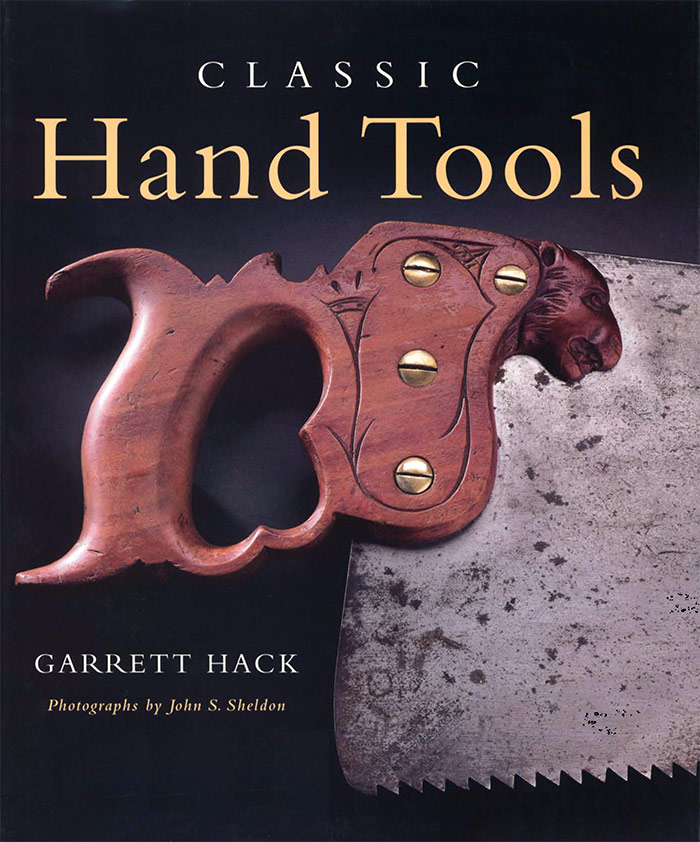

Excerpted from Classic Hand Tools (The Taunton Press, 1999) by Garrett Hack.

Excerpted from Classic Hand Tools (The Taunton Press, 1999) by Garrett Hack.

Available at Amazon.com.

|

Webinar: The history of Bailey handplanesReplay Join Joshua Clark for a fascinating look at the history of handplanes, and the progression of the Stanley plane through the decades. |

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in