Nancy Hiller’s Reality Check(list)

If you’re thinking of turning your passion into a profession you should take a deep look at what is involved in running a legitimate business.

A few weeks ago, on a rainy day that put the kibosh on his regular work plans, the guy who runs one of my favorite local sawmills delivered a load of boards to my shop. After all the lumber was safely inside, we spent a few minutes talking. “A buddy of mine’s going to quit his job and take up cabinetmaking full time,” he told me. “I’d love for him to come and spend a few hours with you so you could give him some tips and show him some techniques.”

“I can’t do that,” I replied, practically choking on my words. “I can’t take the time.”

I’ve lost track of how many times people have assumed that because I’m self-employed, I can hang out and show them tricks of the trade. I deleted “the,” because no one could teach all the tricks of any trade in a day/week/whatever.

It’s astonishing to me that people can be so clueless about the realities of running a business, but the cluelessness persists, along with certain romantic myths about being a professional woodworker. When your livelihood depends on running a one-person business—and I’m talking about those of us who are earning a bona fide basic livelihood, not running a hobby business, operating an enterprise subsidized by parents/a spouse/a partner, or reinventing ourselves after retirement—your most valuable asset is your time.

Let’s face it. The bar for entering this world is exceedingly low. You don’t even have to know that much about woodworking to pass yourself off as someone who can build basic furniture. You can start up in your garage with a few basic tools and hang out your online shingle. Of course, doing so can land you in a heap o’ legal and financial trouble. While the School of Hard Knocks is certainly one path to learning the ins and outs of professional woodworking, I recommend that you augment this dimension of your education by reading and listening to accounts of others who have many years of experience. Hence this post, the first in a series I’ll be writing over the coming year.

People who haven’t run a business tend to be understandably confused about what business income is and is not. There’s a widespread sense that once you’ve covered the cost of materials, the remaining income from a sale is yours—as in, your pay. You know, your salary. Wages. It’s not.

There are expenses associated with running a business, at least when you run it legally and comply with government regulations. If you don’t pay these before paying yourself, watch out.

Here’s a sample list* of expenses from my own experience, with some of the most typical items at the start and less essential stuff toward the end:

- Shop rent if you don’t work out of your own property. If you do work from your own property, there are still expenses, such as higher property taxes, related to using a building for a business. In some municipalities, zoning even forbids using part of your home to run a business, so be sure to check.

- Business insurance, which includes coverage of your shop building and its contents, liability coverage, insurance of goods in transit, etc. If you’re going to work from your home, be sure to tell your insurance agent. Otherwise, if you have a loss related to your business, your claim could be denied.

- Utilities: electricity, gas, water, phone. Think you can heat your shop cost-free by installing a woodstove? Be sure to check with your insurance company before you buy or install that stove. Many insurers today (mine is one of them) simply will not cover a woodshop that contains a woodstove. Period.

- Health insurance. The individual policies my husband and I have cost $600 and $546 per month respectively in 2017. The deductible for each is a sobering $6500.

- Explosion-proof lighting, venting, and switches for spray rooms. Even if you plan to spray only water-based finishes, discuss this with your insurance agent. My insurance company requires the whole explosion-proof nine yards for any kind of spraying. Underwriters are well aware that once you’re set up to spray, you may be tempted to spray solvent-based finishes. If you submit a claim and the company discovers something you did not disclose to them (even if it’s not specifically related to your claim), the claim may be denied.

- Waste disposal, including special fees for solvents and the like. (Please don’t say you think it’s OK to pour this stuff out on the ground to avoid paying a fee for its safe disposal.)

- Business entity registration with the Secretary of State, with related fees. Mine are biennial.

- Repair and maintenance of equipment; replacement blades, cutters, etc.

- Website-related fees and internet service

- Bank charges for business accounts

- Fees for accepting payments through credit cards or online services such as Paypal

- Legal fees as necessary

- Business tangible property tax, if applicable in your area

- Occasional equipment rental, such as trailers for delivering out-of-state jobs

- Permits and licenses, such as parking permits for regulated areas such as those in the city where I do most of my work

- Accountant’s fees

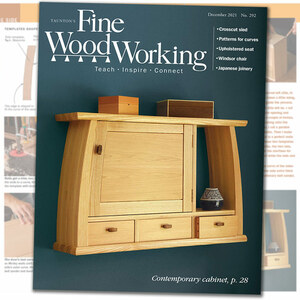

- Subscriptions to trade publications

- Professional organization dues

- Professional photography

- Shipping fees not covered by clients

- Advertising

- Office supplies, photocopying expenses, and printing as needed, such as business cards and letterhead

One monster doesn’t even appear on this list: Social Security and Medicare taxes. If you’re self-employed as a sole proprietor, you will be responsible not just for paying income taxes and the portion of Social Security and Medicare contributions payable by employees, but the portion of Social Security and Medicare taxes ordinarily covered by employers, which are known as matching taxes. ln other words, you will be paying just over 15% in these contributions in addition to whatever you owe in income tax. If you incorporate your business, the corporation pays the employer’s portion, which can be written off as a legitimate business expense … but of course there are other costs, such as legal fees, that come with incorporation.

Keep in mind that you will also need to spend a portion of your time filling out forms and paying these fees and taxes, in addition to sales tax, which “manufacturers,” as those of us who make furniture and cabinetry are classified, are responsible for collecting and submitting to the state (with some exceptions, such as out-of-state sales, or sales made to another party, such as a gallery or furniture store, for resale). You’ll also be dealing with government officials when mistakes arise, as they occasionally will.

Your time—or more precisely, the time you can charge for—is, for the most part, what covers these costs, in addition to providing you with income to live on.

You may think that some of these expenses won’t apply to you because you can do some things, such as bookkeeping and annual tax preparation, for yourself. But doing such work yourself may make less sense than paying a professional so that you can spend that time on your own income-producing work in the shop. There are only so many hours in a day.

If you’re contemplating going pro, I recommend that you use the above list as a worksheet, filling out each line with actual figures for your situation after doing the necessary research. There are free services, such as SCORE (the Senior Corps of Retired Executives) and regional Small Business Development Centers that offer advice on starting and running a business. Inform yourself as well as you can before you take the leap.

*by no means exhaustive, but it’s typical of many one-person businesses.

Nancy Hiller is a professional cabinetmaker who has operated NR Hiller Design, Inc. since 1995. Her most recent book is Making Things Work.

More from Nancy:

- Built-ins that Blend in – Issue #179–Sept/Oct 2005

- Arts and Crafts with an English Accent – Issue #228–Sept/Oct 2012

- Rediscovering Milk Paint – Issue #199–July/Aug 2008

More on going pro:

Comments

Yikes......reading your article just reminded me why I decided to open my shop abroad......it boils down to make it quite difficult, almost impossible to make a living out of woodworking back in the US, hats off for anybody still doing so....

Great read Nancy! These type of business are extremely difficult. I have gone from one man to seven in a very short time, it is completely exhausting. I was exhausted when I was a one man, and I'm exhausted as a crew of 7. Most people don't understand just how hard it is, how demanding commercial and residential clients are, how poor attitudes continue to grow, and how taxes can absolutely crush you even with proper planning. Hats off to you Nancy for sharing this, it's a voice for us!

Ms. Hiller offers very sound advice.

There is one additional observation I would make that is not technical or legal. It is more intrinsic. When you shift from hobby woodworking to professional woodworking, the woodworking becomes your job. It becomes just like any other job job -- you cannot do whatever you feel like doing. You have to do what the job requires.

It is very unlikely that you can make an income sufficient to support your needs by simply making whatever you feel like making. You will be making whatever customers appear to be willing to purchase. You might end up making quite a few items that interest you not in the least.

It takes time to establish yourself with a clientele that can and will pay the prices you need the make the kinds of things you prefer to make.

Franz Klaus' advice is apt: "If you want to have a $100,000 at the end of your first year of woodworking, then be sure to start out with $1,000,000."

Just saying.

What a great blog post!!!!

Very good post Nancy. Here are a couple of things to add to the list of considerations -

1. The cost and risk of bad debt/collection and chasing after your customer to get paid. This can have a major impact on the amount of working capital you may need to effectively run the business and manage cash flow.

2. How to actually price your work. It is simultaneously understandable and shocking to me how few professional woodworkers have any type of sound method for pricing their work. It's not just the cost of the materials and your time. There is overhead, consumable shop supplies, amortization of capital costs like tools, planning and last but not least - contingencies. It's important to try and be competitive when bidding work, but you can't make up negative margins in volume.

It could be frustrating at times when people simply take you for granted especially when they have the wrong perception of you. Being self-employed does not mean that you have all the time in the world to literally do nothing. You are still employed though on your own personal schedule. It gets even more absurd when some of those people expect you to teach them the ropes of starting a business free-of-charge and get upset if you refuse.

I am quickly becoming a fan of your observations and writing style. Thank you for some sobering advice and being blunt about it.

I was pricing something the other day for a customer at my part-time job (at a woodworking store so I can get lower cost wood, other supplies, and meet potential clients) and my boss who is younger, better, and smarter than I am grabbed me quickly and took me aside to tell me to nearly double what he felt I was about to ask. He was right in all cases- I am much happier to make things when I know the compensation is correct and I am often the one who made it incorrect at the outset.

"Hence this post, the first in a series I’ll be writing over the coming year"

Can we get a link to the rest of the series?

Scroll down further or a link to the Pro's Corner is at the top of the page.

Thank you.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in