Problem with a product? Contact the manufacturer

No one is immune to mistakes, so give them an opportunity to make it right.

Who doesn’t know the exasperation of discovering there’s a problem with a finishing product, a piece of shop equipment, or the material you bought for a job?

A few weeks ago I was finishing up some built-in bookcases that called for paint-grade plywood backs. My go-to material for this purpose is ¼-in. poplar-faced veneer-core plywood; I cut it to size and apply it with screws to reinforce the overall structure of the casework, in addition to making a clean-fitting back.

It’s important to note that I buy high-quality American-made plywood manufactured by Columbia Forest Products through my commercial hardwoods supplier, Frank Miller Lumber. If you have access to sheet goods only through a big-box store, make a point of checking the product’s manufacturer; if it’s Columbia Forest Products, you’ll see a stamp with their name on the edge of the sheet (though thin stock typically doesn’t have enough room for the identifying information). As an alternative, check with a knowledgeable member of the store’s staff regarding the manufacturer. This is a good practice regardless of your source; I learned this lesson several years ago at a store that did not stock CFP plywood — the face veneer was so thin that I could literally see through it to the substrate.

It’s important to note that I buy high-quality American-made plywood manufactured by Columbia Forest Products through my commercial hardwoods supplier, Frank Miller Lumber. If you have access to sheet goods only through a big-box store, make a point of checking the product’s manufacturer; if it’s Columbia Forest Products, you’ll see a stamp with their name on the edge of the sheet (though thin stock typically doesn’t have enough room for the identifying information). As an alternative, check with a knowledgeable member of the store’s staff regarding the manufacturer. This is a good practice regardless of your source; I learned this lesson several years ago at a store that did not stock CFP plywood — the face veneer was so thin that I could literally see through it to the substrate.

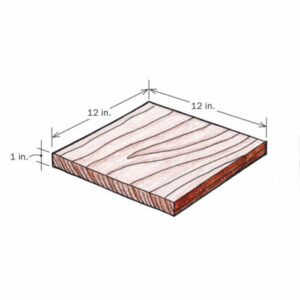

For this job I needed three full sheets. I had ordered all the materials for the job weeks earlier and had the ¼-in. sheets on a pile weighed down by a couple of ¾-in. sheets to keep them perfectly flat. When I pulled them out, I saw that all three were significantly bowed – we’re talking banana-shaped. I needed to rip them to width, then cut them to length.

I was not happy. As I contemplated the safest way to rip the sheets based on experience, I reminded myself to be extra careful about keeping the edge tight against the rip fence (harder to do when you’re ripping something curved). Instead of simply pushing a flat sheet of plywood across the tablesaw bed, I would need to feed it into the blade in a rolling movement, keeping the bottom of the curve facedown; any attempt to rip the sheets the other way up (at least, without a helper to press the sheet down flat as I fed it through) would have been far more dangerous.

After ripping the sheets, I thought about how best to cut them to length. I bought my SawStop slider several years ago for just this purpose, but there was no way I could crosscut such a bowed piece safely on the tablesaw without taking the time to figure out a surefire way to keep the 8-ft. sheet flat. I cut each sheet to length with a handsaw.

What really concerned me was not the inconvenience I experienced, but the thought that someone less experienced could be seriously injured if they didn’t understand how to cut such bowed sheets safely. So I called Frank Miller Lumber, knowing that any complaint about product quality would have to go through them, not the product’s manufacturer. They contacted Bob Stiles at Columbia Forest Products, who called me right away. I explained the problem, along with my concern regarding the safety in using such bowed sheets.

Bob’s approach was methodical. The first question: Was the problem due to improper storage that had caused the bowing, or was it due to how the sheets had been manufactured? Given that I had kept the sheets perfectly flat in my shop, and knowing how careful the people at Frank Miller Lumber are to store their inventory properly, we suspected the manufacturing was at fault. Bowing is more likely in thin products; in this case, the sheets have just three plies.

He suspected an imbalance in the plywood core and explained that most of their products are manufactured in southern states; the material likely had a higher than ideal moisture content. He also shed light on why all three sheets had the same bow: They manufacture in batches, which leads to batch variation. Sometimes I get multiple sheets of prefinished plywood for kitchen cabinets that are faced with gorgeous bird’s-eye maple that seems too pretty for a cabinet interior; this time, I got the short straw.

Whenever you’re faced with a problematic product, Bob said, it’s best to contact the retailer where you bought the product right away, asking them to put you in touch with the manufacturer so they can replace the defective material. My sheets were fine for bookcase backs that would be screwed in place. Bob points out that “manufacturers typically only warranty the value of the material they provide, and accept returns on defective panels. Some kind of extended warranty based on further production on these panels, beyond their value, is not part of that warranty.” So the onus is on each of us to inspect materials when we get them and request replacement when there are problems.

No one likes to get faulty materials. In the best case, they can cause inefficiency or delays in completing a job; in less benign cases, they can lead to call-backs or even failures in finished work, such as delamination. Along with the rest of us, manufacturers are doing their best to meet the expectations of their products consistent with their price point and claims about quality. No one is immune to making mistakes. So the next time you find yourself faced with a problem, contact the manufacturer and give them the opportunity to make it right.

Comments

Good One!

Being knowledgable, polite and determined will get the vast majority of your your issues resolved.

It's nice that Tony allows you to work in his shop.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in