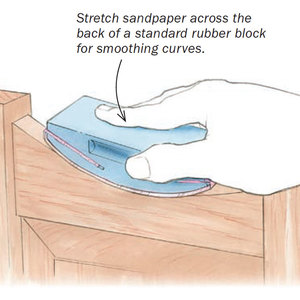

Q&A: Sanding to 500 grit

One reader asks Chris Becksvoort if sanding too fine will interfere with finishing.

I read with interest Christian Becksvoort’s article on belt sanders (FWW #277). He provides an excellent rationale for the belt sander as a useful shop tool, but I was surprised by his method. He advocates sanding through 500 grit and then polishing the wood further with 0000 steel wool. In fact, the photos illustrate this being done on apparently unfinished wood, but many

authors (including in the pages of Fine Woodworking) have argued against ultrafine sanding because it can interfere with the subsequent finishing process. How do I reconcile these two pieces of conflicting advice?

—Michael S. Grace, professor emeritus, Florida Institute of Technology

Chris Becksvoort replies: Thank you for your enlightening question. I’ll give you my interpretation based on more than five decades of working with cherry. As with anything else, it’s a trade-off.

The advantages of sanding to 100 or 120 grit are that A) the rougher surface makes it easier for surface finishes to adhere, B) it makes it easier for stains to penetrate, and C) it saves time and money.

On the other hand, sanding to 400 or 500 grit makes for a better shine and more clarity of grain, especially with oil finishes. For years I’ve had inexperienced woodworkers ask me how to get rid of “blotch” in cherry. I was a bit baffled by the term until a woodworker showed me a blotched cherry drawer. It was cherry sanded only to 120 grit, obscuring and “fuzzying” the figure in wood. As I’ve often said, I pay extra for figured wood, so I take the time to bring out the chatoyance by proper sanding way beyond 100.

It’s very much like planing a board with a toothed blade, leaving a fuzzy surface, vs. planing a board with a welltuned plane, which leaves you that smooth, reflective surface.

From Fine Woodworking #283

-Looking for a deeper dive, including oak and maple? Check out Ari Tuckman’s article in issue #189, When To Stop Sanding.

|

Great Results With A Belt Sander |

|

Tips For Sanding Basics |

|

Sanding Fids |

Comments

As one who also sands to higher grits as well as hand planes final surfaces I will chime in. I understand the attraction or value of stopping your surface preparation protocol at a lower grit. A colored surface that will receive 4 mil or more of urethane or lacquer topcoat will look and feel smooth even if you stop at a low grit. It does not, however have the look I am after.

A No. 4 smoother leaves a much . . . well . . . smoother surface than even 400 grit on a ROS so you can see where the two camps may part ways. Neither is right or wrong and I do not believe you need to reconcile the two schools of thought. Although you may need to choose one for a given piece.

These are just different approaches. I prepare surfaces to a smoother point than some. I like the visual depth I get after the finishing process. I too use figured woods in many pieces and want that natural look to shine through. A stained surface with a nice topcoat also looks good. It is what you see on most commercial furniture.

Personally I have never had a finishing issue that I can attribute to sanding to a certain grit.

Finishing has much more to do with chemistry than it does with the mechanical properties of how rough of a surface you apply your product to.

Many of the age old tips like "leave it rough so the finish has something to grab on to" are for the most part myth, with very little science, if any, behind their rationale. Most of the time these type of tips, or myths as I call them, are a no harm, no foul scenario. Modern finishes seem to adhere just fine with a minimal amount of effort no matter what surface they're being applied to, so every can take comfort that their method worked. The fact that today's finishes are so forgiving, only helps to perpetuate these type of myths.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in