Trust your eye

Bill Pavlak shows you a few simple ways you can train your eye to gauge small distances and simple spatial relationships.

Over the past two years, I’ve spent more time carving and shaping wood than I’ve spent joining it together. As I begin work on a complex, unornamented table, that trend is changing and with it my mindset and the tools on my bench. The biggest shift comes in how I measure parts and judge my progress. Rulers, gauges, and the careful transfer of layout lines from one board to another – the normal means for keeping cabinetmakers on track – will hold sway once again. With the carving work, my ruler got dusty just sitting there as my eye made all of the decisions. It was nice, and I was thinking things like “this leaf needs to be a little bigger,” “that cove needs to be a wee bit deeper,” instead of “how many 64ths is just a little bigger than 3/32nds?” To many woodworkers, putting that much trust in the eye is intimidating. We comfort ourselves in the apparent certainty of our measuring tools and their precise judgments. Perhaps we do this so much that we don’t realize how much trust our eye really deserves. In reality, a lot of what we routinely measure could easily be left to our eyes and minds instead of our rulers. Below are a few simple ways you can train and test your eye to gauge small distances and simple spatial relationships. My carving mind and my cabinetmaking mind don’t need to be two separate things.

The Built-in Ruler

During my first week in the Hay shop 15 years ago, I was planing some walnut for Mack Headley, the shop master. He was still designing the piece and wasn’t certain about the thickness yet, but told me to take it down to 7/8 in. and let him have a look. That instruction was a demonstration in eye judgment itself. Regardless, I called Mack over to look when I hit 7/8 in., but he just asked me to hold the board up instead. Then, from the other side of the room, he casually said, “that looks good, but maybe take off another tenth of an inch.” While my mouth was forming the word “okay,” my brain was wondering “what the $%#@ is 1/10 of an inch, how does one see that from 25 feet away, and do I even belong in this shop?” I quickly came to learn two things. A woodworker memorizes their most used measurements without even trying and one side of Mack’s rule was graduated in tenths of an inch. The ruler becomes built into the eye.

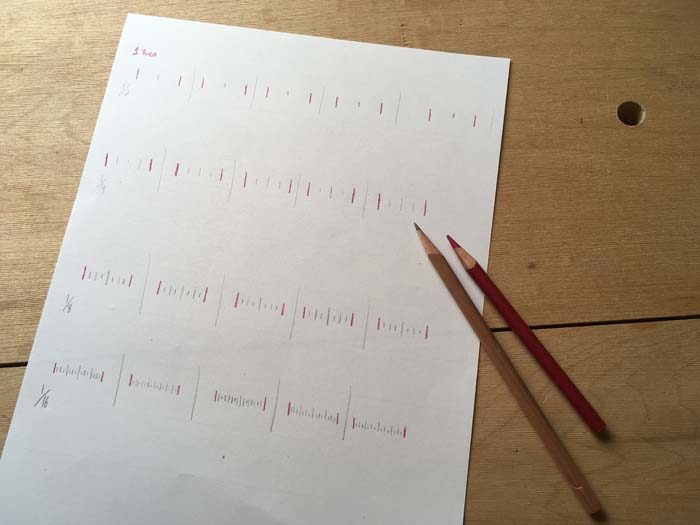

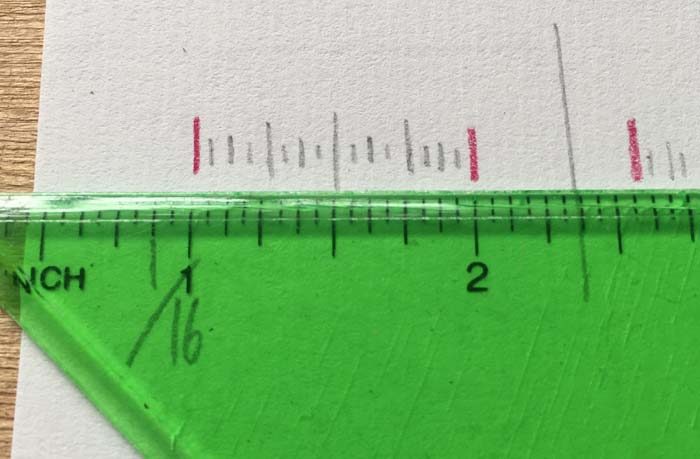

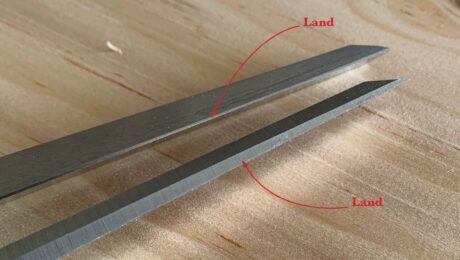

After that experience, I developed a little game that became a habit, a good one. I was not concerned with tenths, but could I accurately see a 1/4 or an 1/8, or tell the difference between 5/16 and 1/4? I started testing myself by setting my marking gauge entirely by eye and then checking it against my ruler. I discovered that I was better than I thought; I could see quarters well. Within a few months, my eighths and sixteenths under an inch were becoming accurate. I still set my gauge by eye and tighten the screw just a little, then check my accuracy and make any adjustments before locking the screw down tight. Generally, I’m spot on or within 1/64 in. of where I need to be. It takes no extra time to do this and what started as a nice eye-training game has become a welcome affirmation: I can trust my eye. Memorizing the divisions of an inch down to 1/16 will not only pay big dividends as a more efficient maker, but it will also help develop your mind for design. Sometimes a 1/4-in.-thick drawer side looks okay, but at 3/16 in. it gains an air of elegance. Becoming sensitive to those subtle differences among measurements is a worthy effort.

Dividing Lines

Most woodworkers can see these dimensions quite well, though some may not believe it. If you’re a newcomer or need a little help, the next basic exercises can help. Draw a couple of lines an inch apart. Do that a few times and then put your ruler away. Now, divide each of those inches in half by eye. Check your work with a ruler or dividers and keep going until you can halve that inch accurately with some consistency. Next, divide that half into quarters and then the quarters into eighths and so on. Find the time to do this every so often until you have it down (nobody will notice that you’re doing this instead of paying attention in your next Zoom meeting). Not only will this cement the basic divisions of an inch into your head, it will also get you used to dividing any space in half. If I’m carving a small acanthus leaf for example, I’m not going to measure half the width to lay out the central vein with anything other than my eye. Like on period work, the results are not always perfect, but it almost never matters.

This same exercise can be used to great effect for dividing spaces in thirds. Draw out an inch or something a little larger a few times and then practice breaking that down into thirds by eye and check your work with dividers. Next, move up to larger spaces like (4-6 inches) and do the same. Thirds play such an important role in design work, so learning to see them clearly will not be wasted effort.

Dovetail These Lessons Together

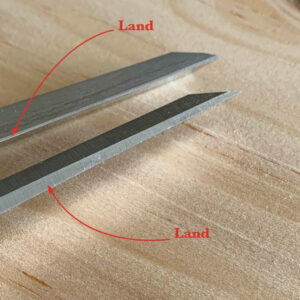

Like most woodworkers, I remember the first time I watched Frank Klausz cut dovetails (it was on VHS, not YouTube). I was certainly impressed by his speed, but I remember being most inspired by the fact that he laid out the joint (except for the baseline) entirely by eye. Even if you don’t dovetail this way, it’s a great eye training exercise. Grab a board that’s about 6 in. wide and make like you’re going to saw some pins or tails into it, but use your pencil instead of your saw to start. The rulers, dividers, or chisels you like to use to lay out joints can take a break. I’m a pins first dovetailer, so that’s what I’m showing here, but like with all things dovetail, it doesn’t matter if you go tails first. Start by marking the location of the half pins at either end of the board using your eye to make them close to equal in width. Now, determine how many full pins you want in between and divide up the space by eye. Don’t worry about being exactly even, just make something that looks evenly spaced. But what about making the spaces agree with the size of my chisels so I can work more efficiently? Well, remember how you’ve memorized the size of the spaces on your ruler? You most likely have a pretty good visual memory of your chisels too, so think of that as you’re laying out the joint. Trust yourself and go for it.

Laying out your pins or tails can be a perfect combination of dividing spaces and seeing certain dimensions accurately. This is how I lay out most of my drawer dovetails and I’ve found it to be a very efficient approach that gives me the kinds of results that I frequently see on period furniture. Try this a few times and check your accuracy. You may be pleasantly surprised by the results. If you hand cut your dovetails and mark your pins directly onto your tail board or vice versa, you won’t need to worry about slight irregularities in your spacing. One last thing: hide your bevel gauge and lay out the angles by eye too. Once again, if you’ve cut dovetails before, you’ve likely developed a keen sense of a proper angle.

Ultimately, learning to trust your eye is about gaining a little experience and then placing enough value on that experience to trust yourself. This is not mystical stuff. You don’t need the experience of Frank Klausz or the power of the Force. There are plenty of times when measuring is essential, but with most one-off furniture work the eye can take you far. Its biggest problem is often the brain that it’s connected to. Don’t sell yourself short or let doubt get in the way. Trust your eye. If you cannot, train it until you can.

Comments

Nice article. Our eyes are capable of doing wonderful things. They are great at dividing things in half, or figuring out the center of something.

Will Neptune is fond of telling how telling the exact size of a random drill bit is hard. But dump all 64 drill bits from a 1/64 to 1" on the table, and we can easily areange them in perfect ascending order. Its not the size that matters, it's the difference in size.

I was hanging a mirror at the end of a hallway, just eyeballing the center of the wall, when my wife stopped me and insisted I measure to make sure it was centered. I was off by 1/8". It is remarkable how capable our vision can be.

Having been for many years seduced by the idea that a better tool would make me a better woodworker, I now understand that the "better tool" I really need to rely on is me, and I need to be as sharp as my chisels. For me, this only comes with desire for improvement, hours of practice and that elusive state of "mindfulness", something I can't even define.

When I first read about splitting a pencil line with my saw kerf, I wondered how such foolishness could make it into a reputable woodworking magazine. How I underestimated the precision that the human tool can achieve. And as my vision and motor skills have declined with age, I can see that the precision is not affected, but rather comes from a different part of my "machinery."

There's a story in one of the Zen books: a carpenter was working on a tea house for a prominent tea master. They were hanging a scroll and a master was like "a little bit to the left, a little bit more, no, that's too much, this is ok, now a bit higher, a bit more, yet more, no, this is too much, please lower" and so on. A carpenter decided to pretend he lost the mark just to figure whether the master is just messing around. The story says that they started over and the new mark was within one bu (~0.1") from the original.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in