Within reason, size doesn’t matter

There's almost always some wiggle room when it comes to sizing parts for a project.

On cutlists/stock lists/schedules, I see some of the numbers as prescriptive and some as approximations – but most of all, a cutlist serves as a guide to help me make the most efficient use of my time and materials. So in general, I find cutlists to be useful – but like any tool, they can also hurt you, or limit what you think you can get away with.

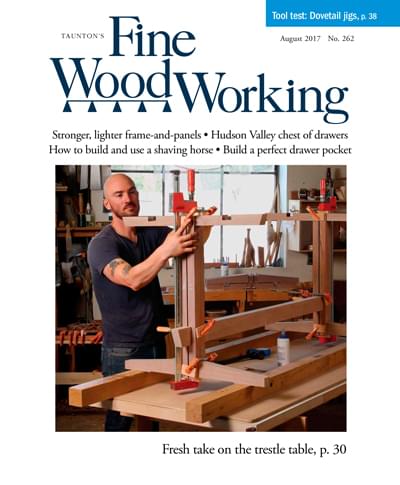

For example, to prepare for a recent tool chest build, I went to the cellar (where we store wood) before simply heading to the lumberyard, knowing I might have some suitable stock left over from an earlier project. My cutlist (shown above) specifies 3/4-in.-thick stock at 11-1/4-in.-wide for the main carcase (a dimensional lumber size, to make the project accessible to those without a jointer and planer). The widest 4/4 suitable stock I had on hand was just a hair more than 11-1/4 in. wide, and needed a few passes over the jointer and through the planer to straighten it, flatten it, and clean off the fuzz. So I cut all my pieces about 1-1/2 in. overlong, and went to work. By the time I was done processing the pine, it was just shy of 3/4 in. thick. Losing 1/8 in. front-to-back in the finished chest won’t matter, and for this project, slightly thinner stock than specified is no problem.

So, by adjusting my stock needs to fit what I had available, I saved money as well as time, and it will make no difference to this finished project. In fact, slight adjustments make no difference to most projects – the possible exceptions being built-in cabinets and bookshelves (but even there, there’s some wiggle room if you’re using a face frame).

After the wood is surfaced, my next step is to cut the pieces to size … sort of. Oftentimes sizes can shift a little as you work, so if you cut all the parts to size before assembly, odds are good that down the line in the build, something won’t fit quite right. So, I look closely at the list to see what pieces have to match perfectly in length, and cut all those at the same time. In the example above, the bottom, front, bottom lip, and fall front all have to be 27 in. long – so I set the stop on the crosscut sled once for those, and make the cuts. And I highlight them in pink so I don’t miss one. But oh dear…I made them all just a hair overlong, as you can see below. But oh well – a 32nd of an inch matters not a bit.

The sides, bottom, and shelf all have to be 11-1/4 in. wide, or in the case of my most recent build, 11-1/8 in. wide (the yellow highlighter), because that’s what I was left with after surfacing the lumber and cutting the board from which those came to the widest possible width.

As a result, the final width of the lid will also need to be 1/8 in. narrower – but instead of calculating that, I glue up the lid both overwide and overlong. I’ll show it to the finished carcase before final sizing – that way I get a perfect fit.

The same goes for the front and fall front. Unless I cut my shelf dadoes in the exact perfect location, the front that covers that shelf might need to be a bit narrower or wider, so by leaving it overwide, I save myself a headache later. And from that follows the width of the “fall front” – again, overwide is excellent insurance. I always measure from the work (or better yet, mark directly from the work instead of measuring).

The other thing I keep in mind as I’m choosing my pieces is final shape. The sides get cut at an angle, which allowed me to use a piece that at first glance would end up too short when cut to length. The cutlist says 25 in. – but that’s at the back corner (and actually it’s 1 in., overlong). At the front corner, it ends up at about 17-1/2 in.

All this is to say don’t fret if your stock and its dimensions aren’t perfect. Just start building. The only people who care about exact sizes are engineers and patternmakers…and magazine editors when they’re checking drawings against what it says in the text (which in my experience is where any errors are sure to occur).

Comments

I saw the headline, and knew it was you.

Length, width and grain direction as it relates to cutting lists recently confused me. It is possible for width to be longer than length. For instance page 35 of the Nov/Dec issue shows the bottom and top of the desktop organizer, illustrating width being longer than length because of grain direction. The forum straightened me out thanks to Mike101 and Dave Richards.

"It is possible for width to be longer than length."

That's very true. It doesn't happen all that often but it does. Perhaps the most common place you'll see this is in traditionally made drawers with solid wood bottoms. The grain runs across the width of the drawer so when the bottom expands with humidity changes, it can expand out the back rather than pushing the drawer sides out. In skinny drawers the width of the bottom will be greater than the length.

It's helpful to have a standard dimensioning method to make that clear.

Glad I was able to help.

Cultists almost always have dimensions of the boards related to grain. Length is along the grain, width across it.

Dimension for a finished piece, such as the width and length of a table, don't follow the same "rules." But they are usually evident from a picture.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in